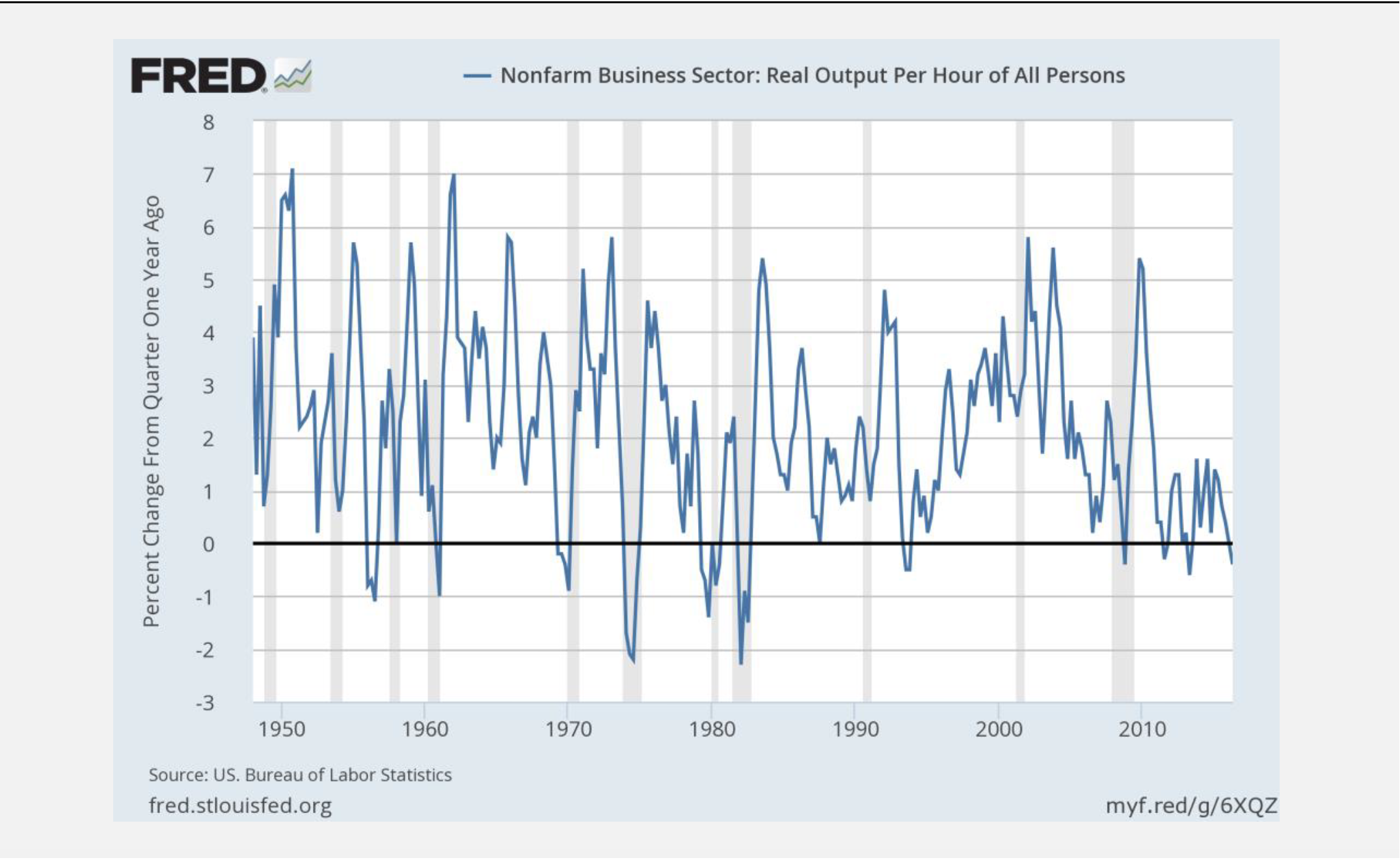

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), multifactor productivity growth was negative in 2016, for the first time since the global financial crisis. That data suggests an acceleration of a long-term downward trend, so the current productivity contraction cannot be written off as a one-time event. For context, productivity growth average 1.25% per annum between 2006 and 2015, roughly half the 2.5% annual figure observed between 1949 and 2005. How to explain the slow-down?

While calling productivity growth a “key uncertainty for the U.S. economy,” Janet Yellen, acting chairman of the U.S. Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) acknowledged that “economists are divided” on the issue, saying: “Some are relatively optimistic, pointing to the continuing pace of innovations that promise revolutionary technologies, from genetically tailored medical therapies to self-driving cars. Others believe that the low-hanging fruit of innovation largely has been picked and that there is simply less scope for further gains.”[1] Confusion in economic circles has, in turn, led to sizable forecast misses. Ben Bernanke, former FOMC chairman highlighted this point recently: “It has not been lost on Fed policymakers that the world looks significantly different in some ways than they thought just a few years ago.” Bernanke added: “For example, in 2009, leading scholars were predicting productivity growth in the coming years of about 2% per annum; in fact, growth in output per hour worked has recently been closer to half a percent per year.”[2]

But, shouldn’t faster and/or better technologies lead to productivity gains, as Yellen suggests? Not exactly. Defined as output per hour per worker, productivity measures overall efficiency and not maximum speed, so it is a function of technology adoption, rather than advancement. This is the point missed by policy-makers, and it explains why mainstream economic forecasts have routinely missed-the-mark. Have you ever been hiking with a group of friends or driven a car on a highway? Pace is determined by the slowest participant and not the fastest, correct? Consider the closed 4-wall setting of a company in the newspaper publishing sector, an industry in transition where swings in productivity are easily-observed. Would newspapers be more productive, if publishers exited print editions altogether and focused their resources entirely on a single digital product? Absolutely, sizable productivity gains will be realized in the future, when publishers eliminate printing presses and delivery trucks; a point that will receive universal agreement from economists. But, what would happen to the cash flow from print subscribers and the revenue earned from advertisers catering to said readers? Profit would go to zero at a time when the price-points on print products (both subscriber and advertiser) are higher than their digital counterpart. Would you throw away good money because of weak productivity figures? This is not rocket science. The situation persists because of the large cohort of (mostly older) consumers, who have savings and a willingness to pay for the higher-priced physical product. Advertisers are further willing to pay more for print subscribers (even though their numbers are declining) because their savings can be easily converted into retail purchases. The same cannot be said of the growing pool of Millennials.

The newspaper example tells us that firm efficiencies are highest when the skillsets/habits of consumers are most alike, a notion that makes sense within the context of systems/processes, where bottlenecks routinely determine total throughput. The pace of productivity can be expected to mirror the ‘S-Curve’ adoption path demarcated in the Diffusion of Innovation Theory, where the gap between early and late adopters is understood to narrow, when rising economies-of-scale allow for lower prices. Ultimately, the more people buying/working in a similar fashion, the more productive the operation. To that end, outsized increases in US productivity between 1994-2003 that averaged 2.8% annually – and led Alan Greenspan to declare a “productivity miracle” had taken place in 1999 – coincide with a period when a single generation of workers (e.g., Baby Boomers) commanded nearly half the labor-force. Data from Pew Research (see Exhibit 2) shows the Baby Boomer generation accounting for 49% of the total workforce in 1995, compared with 31% for Generation X and 18% for the Silent Generation. Weak productivity gains are then observable when the labor force share is more equally dispersed among generations and no single cohort has a dominant position. This is evident in 2015 data, when the Millennial generation reached 34% of the U.S. labor force, which is in line with Generation X (34%) and the Baby Boomers (29%). The same labor-force dynamics were further also in place in the 1970s, when productivity gains were last reversed.

Are you surprised to hear a workforce becomes less productive as it ages? You can’t teach an old dog new tricks, right? The link between shifting labor-force age cohorts and changes in productivity becomes evident when U.S. data is viewed within an international context. After all, we are not dealing with an American phenomenon. Dartmouth economist James Feyrer (2005) has found a direct relationship (in data across 19 advanced economies) between changes in the proportion of workers between the ages of 40-49 and economic productivity, with figures showing “a 5% increase in the size of this cohort over a 10-year period is associated with a 1-2% higher productivity growth in each year of the decade.”[3] Studies in Japan support the idea as well, including Kawaguchi et al (2006), who analyzed Japanese employer data from 1993 to 2003 and found the seniority-productivity profile to exhibit a concave form, with productivity peaking at roughly 20 years of experience or between ages 40 and 50.[4] More recently, a study from Maestas et al (2016) has found that a 10% rise in the share of the U.S. population over the age of 60 to be associated with a 5.5% reduction in gross domestic product (GDP), where 2/3 of the loss is attributable to productivity declines and the remaining to a slower-growing workforce. The authors further conclude aging will reduce total U.S. GDP growth between 2010-2020 by 1.2 percentage points per year and that productivity will drive 2/3 of the fall-off.[5]

While no consensus exists among economists on the cause of the recent productivity slow-down, the connection between GDP and productivity is well understood. Assuming no new capital investment or man-hours worked, GDP can only grow if (a) there are productivity increases from existing workers and/or (b) the number of workers earning wages increases. We also have a firm sense for the forward trend-line in US labor-force growth the labor-force: between 2016 and 2020 the US labor force is forecasted to grow annually at just 0.2%, less than half the 0.5% figure between 2005 and 2015 and well below the 1.7% annual average between 1955-2004. The decline in labor-force growth matters because a 1 percentage point decline in labor-force growth is associated with an equal reduction in GDP growth, according to Ruchir Sharma, so productivity increases (rather than decreases) will be required simply to maintain the 2.1% GDP growth average recorded in the most recent US economic recovery.[6] That was the message from The McKinsey Global Institute (Exhibit 4), which highlighted the increasing need for productivity gains, saying: “Even if productivity were to grow at the (rapid) 1.8% annual rate of the past 50-years, the rate of GDP growth would decline by 40% over the next 50-years.”[7] Unfortunately, productivity gains cannot be pulled forward into the present forecast period, by lowering interest rates to spawn capital investment.

Taken together, the demographic profile of the US labor force – where 10,000 Baby Boomers will be retiring daily through 2028 – suggests negligible (if any) productivity increases through 2020.[8] That’s our base case scenario, and it means that further downward revisions should be expected from the FOMC, which lowered its 3-year GDP forecast to 2% per annum in recognition of productivity weakness observed in the last several quarters. The ‘good news’ is that productivity increases will come, and growth will return on the backside, but only when technology improvements are widely disseminated throughout the labor force in the next-5 years. Make no mistake – future productivity gains will be sizable and (contrary to the view of economist Robert Gordon) will be life-changing. Imagine how much more efficient everyday life will be when driverless cars are widely-adopted and consider the cash savings that will be realized from wasted time spent in traffic, increased mobility for the elderly, and rapid ambulance times.[9]

Exhibit 1.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Exhibit 2.

Source: Pew Research.

Exhibit 3.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Exhibit 4.

Source: The McKinsey Global Institute.

[1] Yellen, Janet. “Current Conditions and the Outlook for the U.S. Economy.” Speech at The World Affairs Council of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, June 6, 2016.

[2] Bernanke, Ben. “The Fed’s Shifting Perspective on the Economy and Its Implications for Monetary Policy.” Brookings Institute, August 8, 2016.

[3] Feyrer, James. “Demographics and Productivity.” Dartmouth College, November 15, 2005.

[4] Kawaguchi, Faji, Ryo Kambayashi, Young Gak Kim, Heog Ug Kwon, Satoshi Shimizutani, Kyoji Fukao, Tatsuji Makino and Izumi Yokoyama. “Does Seniority-based Wage Differ from Productivity?” Hi-Stat Discussion Paper Series 189, 2006.

[5] Maestas, Nicole, and Mullen, Kathleen, and Powell, David. “The Effect of Population Aging on Economic Growth, the Labor Force and Productivity.” RAND Working Paper Series WR-1063-1, August 19, 2016.

[6] Sharma, Ruchir. The Rise and Fall of Nations. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

[7] “Global Growth: Can Productivity Save the Day in an Aging World?” McKinsey Global Institute, January 2015.

[8] “Baby Boomers Retire.” Pew Research Center, December 29, 2010.

[9] Gordon, Robert J. The Rise and Fall of American Growth. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2016.